Your cart is empty.

Your cart is empty.

Festival City Stories

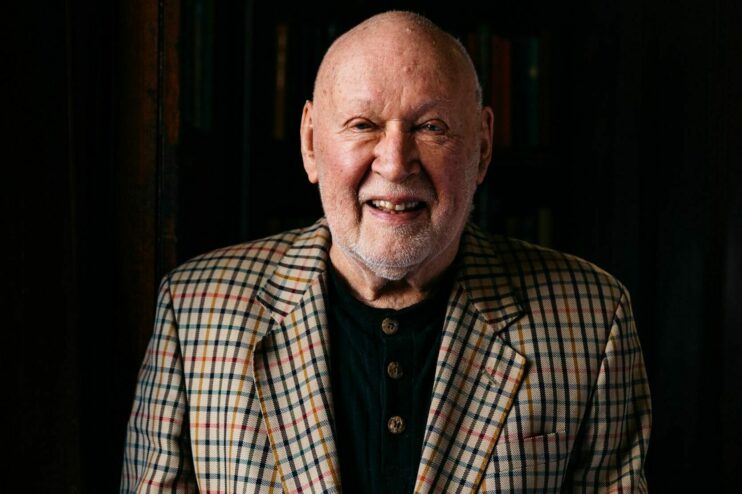

Handpicked by Don Dunstan to lead the Adelaide Festival and Adelaide Festival Centre in the 1970s, veteran arts administrator and self-described ‘artistic dictator’ Anthony Steel both challenged and delighted audiences in his mission to turn Adelaide into a festival state.

“Generally speaking, if I had annoyed and outraged the audiences, I was most happy,” he says now. “Because I was all the time attempting to bring them along on a journey – and succeeded in doing so.”

Steel’s own journey to Adelaide began in 1972 when he attended a meeting with then-Premier Don Dunstan at London’s South Australia House. Steel had been making a name for himself in England working with the London Mozart Players, London Symphony Orchestra and Festival Hall, which put him on the radar of Dunstan’s arts department as it searched for a general manager for the Adelaide Festival Centre.

“They’d subsequently said they were also looking for somebody to run the Festival, so I said to myself, ‘If I’m going to go all that way to a place I’ve never heard of, I want both those jobs.’ I said this fairly directly to Don, and within 20 minutes he’d said, ‘All right.’ So I was sunk.”

Touching down in Adelaide, he encountered a city in “terrific contrast” to London. The Festival had been running since 1960 and Steel saw great potential — but also a fog of parochialism and cultural cringe. “As far as I could see, there wasn’t a great deal going on in a proper, full, professional manner except for the Festival, and the Festival had run into trouble in the last two Festivals.”

“They were looking for somebody with a new approach,” he says. “It had had a lot of very good people coming to it, but they’d mostly been from Britain – not all, by any means, but mostly – and they’d all been pretty traditional, and I devised a policy that I thought made complete sense and then tried to sell it to the public.”

“I became known as a ‘proselytising Modernist’, which I rather liked, and I set out to bring to Adelaide as much, for want of a better word, ‘cutting edge’ performing arts as I could find around the world. To have foreign language theatre in those days, particularly when there was no simultaneous translation or surtitles, was a pretty adventurous thing to do.”

“Adelaide was the only festival in the country that anyone took any notice of, so there was every possibility to strike out and bring what you wanted,” he says. “That enabled you to bring some pretty unusual work, certainly unusual to Adelaide – indeed, unusual to Australia.

Audiences might not have initially understood what Steel was trying to do, but he was reassured to find they were, for the most part, game to find out. “They would come anyway because it was the Adelaide Festival, whether they liked it or disliked it, so you had a captive audience. And bit by bit they became accustomed to new work and then, when other art centres opened [and] other festivals started around the country, even more work came and audiences all around the country got more used to new work.”

But his tenure wasn’t entirely without controversy; Steel’s artistic choices and sense of conviction created an oft-contentious relationship with local critics and the city’s conservative establishment. “I had lots of rows with the critics; I was so rude to them after one Festival that the local branch of their union forbade me from being interviewed for a month, which I thought was terrific,” he recalls with no small amount of glee.

“There was one famous occasion when I brought a play by Steve Berkoff called East that [came] from London. It was full of filthy language and a lot of pretty unpleasant business. Everybody tried to have it stopped,” he says, citing an open letter sent to The Advertiser with 58 signatories calling to ‘Keep Adelaide Clean’. “[The] Opposition’s spokesman for the arts demanded in Parliament that I be dismissed for bringing this filth to Adelaide. He hadn’t seen it either, of course – it hadn’t arrived here yet. This was the sort of shock that I was trying to provide, successfully, I think,” he says. And once they had seen it? “Oh, of course, we had to extend the season.”

Steel directed three festivals in his initial tenure, and returned to helm two more in 1984 and 1986. He still lives in Adelaide today, and nearly 50 years after his arrival remains proud of how the Dunstan era helped shake up Adelaide’s (and Australia’s) relationship with the arts. “[Dunstan] knew that one very important thing for [the citizens of South Australia], whether they knew it or not, was Culture with a capital C. And he just did everything he possibly could to make certain that the arts were well looked after in this State. There’s never been anybody like him and there’ll probably never be anybody like him again.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

This article is part of the Festival City Stories series, a collection of reflections about Adelaide made by the people who make this a festival place. The project was funded through the Department of Premier and Cabinet, Arts South Australia, Arts Recovery Fund, and delivered in partnership with the State Library of South Australia.

Written by: Walter Marsh

Photography by: Sia Duff

With so much going on in Adelaide, how will you ever keep up? Make sure to never miss a festival beat and sign up to receive the latest about Festival City Adelaide directly to your inbox.